|

||

|

||

|

|

|

Active Hydrogen

Adrenal Extracts

Alanine

Alpha-Linolenic Acid

Alpha-Lipoic Acid

AMP

Amylase Inhibitors

Arginine

Bee Pollen

Beta Carotene

Beta-glucan

Betaine

Beta-Sitosterol

Biotin

Borage Oil

Boron

Bovine Cartilage

Bovine Colostrum

Brewer's Yeast

Bromelain

Calcium

Capsaicin

Carnitine

Carnosine

Chitosan

Chloride

Chlorophyll

Chondroitin

Chromium

CLA

Cobalt

Coenzyme Q10

Copper

Creatine

Cysteine

DHA

DHEA

DMAE

EGCG

Evening Primrose Oil

5-HTP

Fiber (Insoluble)

Fiber (Soluble)

Fish Oil

Flavonoids

Fluoride

Folate

Fumaric Acid

GABA

Gamma-Linolenic Acid

Glucomannan

Glucosamine

Glutamic Acid

Glutamine

Glutathione

Glycine

Grape Seed Extract

Histidine

HMB

Hydroxycitric Acid

Indole

Inosine

Inositol

Iodine

Ipriflavone

Iron

Isoleucine

Lactase

Lecithin

Leucine

Lipase

Lutein

Lycopene

Lysine

Magnesium

Malic Acid

Manganese

Mannose

Melatonin

Methionine

Methoxyisoflavone

Molybdenum

MSM

N-Acetyl Cysteine

NADH

Naringin

Niacin

Octacosanol

Oligosaccharides

Olive Leaf Extract

Ornithine

Oryzanol

PABA

Pancreatic Enzymes

Pantothenic Acid

Phenylalanine

Phosphatidylserine

Phosphorus

Phytic Acid

Policosanol

Potassium

Pregnenolone

Probiotics

Propolis

Psyllium

Pyridoxine

Pyruvate

Quercetin

Resveratrol

Retinol

Riboflavin

Ribose

Royal Jelly

SAMe

Selenium

Shark Cartilage

Silicon

Sodium

Spirulina

Spleen Extracts

St. John's Wort

Strontium

Sulforaphane

Sulfur

Taurine

Thiamine

Tocopherol

Tea Tree Oil

Tyrosine

Usnic Acid

Valine

Vanadium

Vinpocetine

Vitamin A

Vitamin B1

Vitamin B2

Vitamin B3

Vitamin B5

Vitamin B6

Vitamin B9

Vitamin B12

Vitamin C

Vitamin D

Vitamin H

Vitamin K

Whey Protein

Xylitol

Zinc

Abalone Shell (shi jue ming)

Abutilon Seed (dong kui zi) Acanthopanax Bark (wu jia pi) Achyranthes (niu xi) Aconite (fu zi) Acorus (shi chang pu) Adenophora Root (nan sha shen) Agkistrodon (bai hua she) Agrimony (xian he cao) Ailanthus Bark (chun pi) Akebia Fruit (ba yue zha) Albizzia Bark (he huan pi) Albizzia Flower (he huan hua) Alfalfa (medicago sativa) Alisma (ze xie) Aloe (lu hui) Alum (bai fan) Amber (hu po) Ampelopsis (bai lian) Andrographis (chuan xin lian) Anemarrhena (zhi mu) Antelope's Horn (ling yang jiao) Apricot Seed (xing ren) Areca Peel (da fu pi) Areca Seed (bing lang) Arisaema (tian nan xing) Ark Shell (wa leng zi) Arnebia (zi cao or ying zi cao) Arnica (arnica montana) Artichoke Leaves (Cynara scolymus) Ash bark (qin pi) Ashwagandha (withania somniferum) Aster (zi wan) Astragalus (huang qi) Aurantium (zhi ke [qiao]) Bamboo Juice (zhu li) Bamboo Shavings (zhu ru) Belamcanda Rhizome (she gan) Benincasa Peel (dong gua pi) Benincasa Seed (dong gua xi/ren) Benzoin (an xi xiang) Bilberry (yue ju) Biota Leaf (ce bai ye) Biota Seed (bai zi ren) Bitter Melon (ku gua) Bitter Orange Peel (ju hong) Black Cohosh (sheng ma) Black Plum (wu mei) Black Sesame Seed (hei zhi ma) Bletilla (bai ji) Boneset (ze lan) Borax (peng sha) Borneol (bing pian) Bottle Brush (mu zei) Buddleia (mi meng hua) Buffalo Horn (shui niu jiao) Bulrush (pu huang) Bupleurum (chai hu) Burdock (niu bang zi) Camphor (zhang nao) Capillaris (yin chen hao) Cardamon Seed (sha ren) Carpesium (he shi) Cassia Seed (jue ming zi) Catechu (er cha) Cat's Claw (uncaria tomentosa) Cephalanoplos (xiao ji) Celosia Seed (qing xiang zi) Centipede (wu gong) Chaenomeles Fruit(mu gua) Chalcanthite (dan fan) Chebula Fruit (he zi) Chinese Gall (wu bei zi) Chinese Raspberry (fu pen zi) Chrysanthemum (ju hua) Cibotium (gou ji) Cinnabar (zhu sha) Cinnamon (rou gui or gui zhi) Cistanche (rou cong rong) Citron (xiang yuan) Citrus Peel (chen pi) Clam Shell (hai ge ke/qiao) Clematis (wei ling xian) Cloves (ding xiang) Cnidium Seed (she chuang zi) Codonopsis (dang shen) Coix Seed (yi yi ren) Coptis (huang lian) Cordyceps (dong chong) Coriander (hu sui) Corn Silk (yu mi xu) Cornus (shan zhu yu) Corydalis (yan hu suo) Costus (mu xiang) Cranberry (vaccinium macrocarpon) Cremastra (shan ci gu) Croton Seed (ba dou) Curculigo (xian mao) Cuscuta (tu si zi) Cuttlefish Bone (hai piao xiao) Cymbopogon (xiang mao) Cynanchum (bai qian) Cynomorium (suo yang) Cyperus (xiang fu) Dalbergia (jiang xiang) Damiana (turnera diffusa) Dandelion (pu gong ying) Deer Antler (lu rong) Dendrobium (shi hu) Devil's Claw (harpagophytum procumbens) Dianthus (qu mai) Dichroa Root (chang shan) Dittany Bark (bai xian pi) Dong Quai (tang kuei) Dragon Bone (long gu) Dragon's Blood (xue jie) Drynaria (gu sui bu) Dryopteris (guan zhong) Earthworm (di long) Eclipta (han lian cao) Elder (sambucus nigra or sambucus canadensis) Elsholtzia (xiang ru) Ephedra (ma huang) Epimedium (yin yang huo) Erythrina Bark (hai tong pi) Eucalyptus (eucalyptus globulus) Eucommia Bark (du zhong) Eupatorium (pei lan) Euphorbia Root (gan sui or kan sui) Euryale Seed (qian shi) Evodia (wu zhu yu) Fennel (xiao hui xiang) Fenugreek (hu lu ba) Fermented Soybeans (dan dou chi) Flaxseed (ya ma zi) Fo Ti (he shou wu) Forsythia (lian qiao) Frankincense (ru xiang) Fritillaria (chuan bei mu) Gadfly (meng chong) Galanga (gao liang jiang) Galena (mi tuo seng) Gambir (gou teng) Gardenia (zhi zi) Garlic (da suan) Gastrodia (tian ma) Gecko (ge jie) Gelatin (e jiao) Genkwa (yuan hua) Germinated Barley (mai ya) Ginger (gan [sheng] jiang) Ginkgo Biloba (yin xing yi) Ginseng, American (xi yang shen) Ginseng, Asian (dong yang shen) Ginseng, Siberian (wu jia shen) Glehnia (sha shen) Glorybower (chou wu tong) Goldenseal (bai mao liang) Gotu Kola (luei gong gen) Green Tea (lu cha) Gymnema (gymnema sylvestre) Gynostemma (jiao gu lan) Gypsum (shi gao) Halloysite (chi shi zhi) Hawthorn (shan zha) Hemp Seed (huo ma ren) Homalomena (qian nian jian) Honey (feng mi) Honeysuckle Flower (jin yin hua) Honeysuckle Stem (ren dong teng) Houttuynia (yu xing cao) Huperzia (qian ceng ta) Hyacinth Bean (bai bian dou) Hyssop (huo xiang) Ilex (mao dong qing) Imperata (bai mao gen) Indigo (qing dai) Inula (xuan fu hua) Isatis Leaf (da qing ye) Isatis Root (ban lan gen) Java Brucea (ya dan zi) Jujube (da zao) Juncus (deng xin cao) Kadsura Stem (hai feng teng) Katsumadai Seed (cao dou kou) Kelp (kun bu) Knotweed (bian xu) Knoxia root (hong da ji) Kochia (di fu zi) Lapis (meng shi) Leech (shui zhi) Leechee Nut (li zhi he) Leonorus (yi mu cao) Lepidium Seed (ting li zi) Licorice (gan cao) Ligusticum (chuan xiong) Ligustrum (nč zhen zi) Lily Bulb (bai he) Limonite (yu liang shi) Lindera (wu yao) Litsea (bi cheng qie) Lobelia (ban bian lian) Longan (long yan hua [rou]) Lophatherum (dan zhu ye) Loquat Leaf (pi pa ye) Lotus Leaf (he ye) Lotus Node (ou jie) Lotus Seed (lian zi) Lotus Stamen (lian xu) Luffa (si gua luo) Lycium Bark (di gu pi) Lycium Fruit (gou qi zi) Lygodium (hai jin sha) Lysimachia (jin qian cao) Magnetite (ci shi) Magnolia Bark (hou po) Magnolia Flower (xin yi hua) Maitake (grifola frondosa) Marigold (c. officinalis) Massa Fermentata (shen qu) Milk Thistle (silybum marianum) Millettia (ji xue teng) Mint (bo he) Mirabilite (mang xiao) Morinda Root (ba ji tian) Mugwort Leaf (ai ye) Mulberry Bark (sang bai pi) Mulberry Leaf (sang ye) Mulberry Twig (sang zhi) Mullein (jia yan ye) Musk (she xiang) Myrrh (mo yao) Notoginseng (san qi) Notopterygium (qiang huo) Nutmeg (rou dou kou) Oldenlandia (bai hua she she cao) Omphalia (lei wan) Onion (yang cong) Ophicalcite (hua rui shi) Ophiopogon (mai dong) Oroxylum Seed (mu hu die) Oryza (gu ya) Oyster Shell (mu li) Passion Flower (passiflora incarnata) Patrinia (bai jiang cao) Pau D'Arco (tabebuia avellanedae) Peach Seed (tao ren) Pearl (zhen zhu [mu]) Perilla Leaf (su ye) Perilla Seed (su zi) Perilla Stem (su geng) Persimmon (shi di) Pharbitis Seed (qian niu zi) Phaseolus (chi xiao dou) Phellodendron (huang bai) Phragmites (lu gen) Picrorhiza (hu huang lian) Pinellia (ban xia) Pine Knots (song jie) Pipe Fish (hai long) Plantain Seed (che qian zi) Platycodon (jie geng) Polygala (yuan zhi) Polygonatum (huang jing) Polyporus (zhu ling) Poppy Capsule (ying su qiao) Poria (fu ling) Prickly Ash Peel (hua jiao) Prinsepia Seed (rui ren/zi) Prunella (xia ku cao) Prunus Seed (yu li ren) Pseudostellaria (tai zi shen) Psoralea (bu gu zhi) Pueraria (ge gen) Pulsatilla (bai tou weng) Pumice (fu hai shi) Pumpkin Seed (nan gua zi) Purslane (ma chi xian) Pyrite (zi ran tong) Pyrrosia Leaf (shi wei) Quisqualis (shi jun zi) Radish (lai fu zi) Realgar (xiong huang) Red Atractylodes (cang zhu) Red Clover (trifolium pratense) Red Ochre (dai zhe shi) Red Peony (chi shao) Red Sage Root (dan shen) Rehmannia (shu di huang) Reishi (ling zhi) Rhubarb (da huang) Rice Paper Pith (tong cao) Rose (mei gui hua) Rosemary (mi die xiang) Safflower (hong hua) Saffron (fan hong hua) Sandalwood (tan xiang) Sanguisorba Root (di yu) Sappan Wood (su mu) Sargent Gloryvine (hong teng) Saw Palmetto (ju zong lu) Schefflera (qi ye lian) Schisandra (wu wei zi) Schizonepeta (jing jie) Scirpus (san leng) Scopolia (S. carniolica Jacq.) Scorpion (quan xie) Scrophularia (xuan shen) Scutellaria (huang qin) Sea Cucumber (hai shen) Sea Horse (hai ma) Seaweed (hai zao) Selaginella (shi shang bai) Senna (fan xie ye) Shiitake (hua gu) Siegesbeckia (xi xian cao) Siler Root (fang feng) Slippery Elm (ulmus fulva) Smilax (tu fu ling) Smithsonite (lu gan shi) Sophora Flower (huai hua mi) Sophora Root (ku shen) Spirodela (fu ping) Stellaria (yin chai hu) Stemona (bai bu) Stephania (fang ji [han]) Sweet Annie (qing hao) Teasel Root (xu duan) Tiger Bone (hu gu) Torreya Seed (fei zi) Tortoise Plastron (gui ban) Tremella (bai mu er) Trichosanthes Fruit (gua lou) Trichosanthes Root (tian hua fen) Trichosanthes Seed (gua lou ren) Tsaoko Fruit (cao guo) Turmeric (jiang huang) Turtle Shell (bie jia) Tussilago (kuan dong hua) Urtica (xun ma) Uva ursi (arctostaphylos uva-ursi) Vaccaria Seed (wang bu lui xing) Valerian (jie cao) Veratrum (li lu) Viola (zi hua di ding) Vitex (man jing zi) Walnut (hu tao ren) Watermelon (xi gua) White Atractylodes (bai zhu) White Mustard Seed (bai jie ze) White Peony (bai shao) Wild Asparagus (tian men dong) Windmill Palm (zong lu pi/tan) Xanthium (cang er zi) Zedoary (e zhu) |

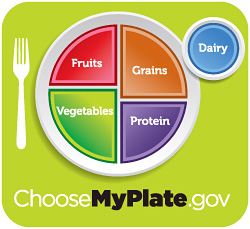

A Pyramid Is Replaced by a Plate

By G. Douglas Andersen, DC, DACBSP, CCN The much-maligned USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) food pyramid has been replaced by a four-quadrant plate. The pyramid had little impact on the average person for the simple reason that people do not think of meals in the form of a pyramid. People also do not think in serving sizes. For example, ask each person at the local submarine sandwich shop if they know the $5 foot-long they just ate had four servings of bread. Better yet, ask health professionals; you'll discover a surprising percentage of the people who should know don't know, either. You could even ask a bonus question like what a serving of grated carrots looks like. But be warned, you'll discover the easy sounding serving of grated carrots question is harder for doctors and therapists to get right than asking them to name an autoimmune disease that attacks joints. In 2005 a redesigned pyramid with vertical bands replaced the pyramid that contained rows of boxes. It continued to provide little value for the average person. I thought it was a step backward from the 1992 version it replaced. I think the plate is a huge improvement over the pyramid. But not everyone agrees. I was moved to write this article after surfing the Web and encountering a good deal of criticism from the alternative health care community when the USDA plate (MyPlate) was unveiled. From a clinician's point of view, I do not think they could have been more wrong. The plate is a way to feed the public information in an easily digestible manner (puns intended). Unlike the pyramid, the plate has a chance to be comprehended by average folks because average folks put their food on plates. In other words, the plate is how people think. Better still, health care professionals can easily customize it for individual patients or even design plates for specific meals. I know it's no secret that the USDA is neither cutting edge nor immune from food industry influence, and it is no secret that the optimal diet is still being debated. This has led to some of the MyPlate criticisms. (Table 1)

I agree this may be confusing to some, but I do not think it will cause a fraction of the confusion the food pyramid did. Furthermore, had they called it "meats," "legumes and nuts" or "meats, nuts and legumes," the complaints would have still rolled in. Even if protein is misunderstood, filling half of the plate with fruits and vegetables won't be. (I was disappointed that "grains" wasn't labeled as "whole grains.") As for the other criticisms, arguments about what is best to eat started as soon as man began to study nutrition. In fact, it ranks just behind religion and politics in its ability to create a heated discussion. Since I have been interested in nutrition, there have been major paradigm shifts, beginning with a researcher named Nathan Pritikin, who improved his own health problems with a very low-fat, low-protein, very high (unrefined) carbohydrate diet. Initially scorned, it was eventually embraced by both allopathic and alternative providers. It also inspired a number of other diets which were variations of his basic idea. Unfortunately, the interpretation of the diet became diluted by the time it reached the general public. Somehow "unrefined carbohydrate" became "any carbohydrate." And when high-carb advocates said you can't get fat eating carbs, the public didn't gorge on the same carbs – greens, beans and colored veggies – as the experts did. Their carbs of choice were huge quantities of breads, bagels and pasta. To make matters even worse, the public put fats like cheese on those carbs before they ate them. The results were record-setting weight gains across the population.

Today, we have a confused public and a philosophical divide between health and nutrition providers across numerous disciplines whenever the topic of "healthiest diet" comes up. So it's really no surprise MyPlate did not satisfy all parties. But those of you who were initially unhappy should take a second look from the point of view of a confused patient and remember that if half of the plate is fruits and vegetables, that's a big step in the right direction. Next month, we will begin a series on what foods the healthiest people around the world actually eat. Dr. G. Douglas Andersen practices in Brea, Calif. He can be contacted via his Web site: www.andersenchiro.com. For more information, including a brief biography, a printable version of this article and a link to previous articles, please visit his columnist page online: www.dynamicchiropractic.com/columnist/andersen. |

Nutritional Wellness News Update:

Other Alternative Health Sites

Toyour Health

ChiroWeb

ChiroFind

Dynamic Chiropractic

DC Practice Insights

Acupuncture Today

Massage Today

Naturopathy Digest

Chiropractic Research Review

Spa Therapy

|

Isaac Newton's Third Law states that "for every action comes and equal and opposite reaction." And in the case of the high-carbohydrate diet, it appeared in the form of Dr. Robert Atkins, a man who attacked carbohydrates with the same ferocity that Pritikin used on fats. He advocated a very low-carbohydrate, high-protein, high-fat diet. Like Pritikin, Dr. Atkins' concept was immediately slammed and he was ridiculed. Partial acceptance took many years and like Pritikin, most of the Atkins acceptance was for variations of the original plan. In the latter case, this meant more fiber and limited saturated fats in the context of a high-protein, high-fat, low-carb meal plan.

Isaac Newton's Third Law states that "for every action comes and equal and opposite reaction." And in the case of the high-carbohydrate diet, it appeared in the form of Dr. Robert Atkins, a man who attacked carbohydrates with the same ferocity that Pritikin used on fats. He advocated a very low-carbohydrate, high-protein, high-fat diet. Like Pritikin, Dr. Atkins' concept was immediately slammed and he was ridiculed. Partial acceptance took many years and like Pritikin, most of the Atkins acceptance was for variations of the original plan. In the latter case, this meant more fiber and limited saturated fats in the context of a high-protein, high-fat, low-carb meal plan.